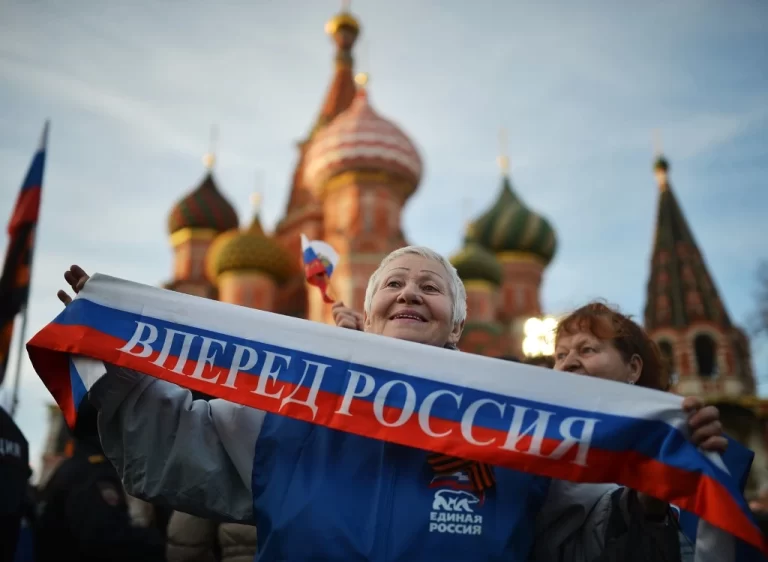

Personal stories are more emotional than propaganda and more convincing than official statistics. Sociologists claim that Russians support the war in Ukraine. Western countries punish them with sanctions and discrimination for it. However, most Russians do not support the war; they adapt to it. The desire to survive is more vital than political beliefs and compassion for Ukrainians among Russians. Let me explain this through the experience of my friend and her family

Why Are Russians Adapting to War in Ukraine?

Personal stories are more emotional than propaganda and more convincing than official statistics. Sociologists claim that Russians support the war in Ukraine. Western countries punish them with sanctions and discrimination for it. However, most Russians do not support the war; they adapt to it. The desire to survive is more vital than political beliefs and compassion for Ukrainians among Russians. Let me explain this through the experience of my friend and her family

Sophia Petrova* and I have been friends for 30 years. We finished school together, celebrated our weddings, and later the births of our children. Together, we experienced February 24, 2022, when our lives dramatically changed.

Sophia is 42 years old. She has lived in Tula, with a population of 480,000, located 190 km South of Moscow. Tula is a city of weapon makers. They produce the Pantsir missile system that participates in the war with Ukraine. Sophia’s husband works as a lawyer in a neighboring region. His company exports grain, including “unfriendly countries,” as Russian authorities say. Sophia is a housewife, and the couple has two children. Before the war, they lived well. The family went on vacations to Europe twice a year and bought expensive clothes and household appliances. Their eldest daughter attended a private school in Austria. Five years ago, the Petrov family realized their dream – they built a large house near Tula and got a dog. The family visited Crimea every year to see Sophia’s husband’s parents. There, they enjoyed kiteboarding and harvested grapes and peaches. The family was happy about the annexation of Crimea in 2014 for practical reasons. It became easier for them to visit their parents via the new Crimean Bridge without border formalities. Sophia even bought an apartment by the sea in Crimea to start a family tourism business. She was delighted and shared photos of their beautiful life on Instagram.

When the war in Ukraine began, many things changed. Trips to Europe and foreign brands became inaccessible for Sophia. Her husband started facing problems at work. They had to bring their daughter back from the Austrian school. Tourists were not rushing to book apartments in the frontline Crimea due to “informational efforts by a neighboring country,” Sophia complained on Instagram. She believes Russians were genuinely discriminated against in Ukraine, as her father-in-law was fired from his job because he was Russian. It is a family legend.

Instead of Europe, Sophia vacations in Thailand or the Russian forest. She severed ties with her childhood friends who left Russia to protest Putin’s regime. She calls herself a patriot who stands with her country despite circumstances. Her husband Igor believes that the Russian government was forced to start the war with Ukraine and that we “don’t know everything” and “it’s not all so straightforward.”

However, the Petrov family does not participate in patriotic actions or collect money to purchase drones for the war. Sophia’s husband is not a soldier, policeman, or government official. From the outside, it seems like millions of Russians pretend nothing is happening, as the Petrovs family. They continue to work, study, go to movies and restaurants, and travel. A similar description of peaceful life in Berlin before World War II in Nazi Germany was given by the American journalist William L. Shirer in his “Berlin Diary.” People avoided craziness by engaging in everyday activities. They did not want to understand the horrors the state perpetrated in their name.

Philosopher Hannah Arendt describes this social phenomenon as “the adoption of manners” by citizens in dictatorial regimes, where people do not embrace the state ideology but conform to new rules. Most Russians believe they cannot influence anything, so they adapt. This is precisely what Sophia Petrova does. Hannah Arendt argues that obedience for an adult signifies support. Therefore, anyone who has not refused to identify with the government shares political responsibility for its crimes. According to sociological surveys, most Russians fall into this category.

In May 2023, according to the data from the only Russian independent pollster, Levada-Center, 76% of Russians supported the war. However, only 20% of Russians feel concern and fear due to the war in Ukraine. Among them, 34% are worried about the military people, 22% are concerned about the domestic and global situation, and another 20% are preoccupied with personal problems.

Why is there such high support for a bloody effort on foreign soil among Russians? It’s because, like Sophia, they have no choice. And the longer the war continues, the more supporters it will gain in Russian society.

After February 24, 2022, Sofia waited to accept the war. She spent sleepless nights crying for three days, saying, “How could this happen?” “What do we do now?” “All our plans are ruined!” But then Sofia pulled herself up.

“We have nowhere to go. We won’t protest because we don’t want to end up in prison. We also don’t have the money or job to leave the country. Who would need us there? So we’ll be on the side we’re on. And we’re in Russia,” she explained in March 2022.

Sofia stopped all discussions about the war and the future of Russia to “avoid getting nervous.” In April 2022, two Pantsir missile systems were stationed near her house for the air defense of Moscow. Sofia fed the military crews sandwiches and allowed them to come to wash up and do laundry. She did this not because she supported the war but because she supported the people she had to survive with.

“Where is the best place for us to go to hide from possible bombings?” Sofia asked the militaries.

“You have military factories all around here. If anything happens, you’ll be the first to get hit, so staying closer to us is better. It will be the safest place near us,” they replied.

There were no discussions between Sofia and the Pantsir crew about “Ukrainian Nazis,” “denazification,” or “demilitarization” of Ukraine. It was only a dialogue between people who, due to their government, faced a common survival problem. Together, they became hostages of a bloody dictatorship. And most people in Russia are in the same situation.

But the problem is that over time, Russian propaganda, anti-Russian Western Sanctions, and discussions of “collective guilt” towards all Russians will turn people like Sofia into staunch supporters of Putin and his war.

For over a year, harsh Western Sanctions have been imposed on Russians. They are denied visas, their bank accounts are blocked, and access to goods is restricted. In other words, Sofia can’t travel abroad and can’t continue her daughter’s education in Austria. Of course, none of this is life-threatening, unlike the shelling of Ukrainian cities by the Russian army. However, neither Sofia, her husband, nor her daughter are personally involved in these attacks. Therefore, they only feel the humiliation of discrimination based on their passport.

Furthermore, the European trend of rejecting everything “Russian” instills deep disappointment in the democratic liberal values of European countries for Sofia. Like other Russians, she is only becoming more convinced of the correctness of Putin’s propaganda that enemies surround Russia.

On its part, the Russian government, through the media, firmly establishes in the minds of Russians a direct connection between the fight of “our grandparents” against the Nazis during the Great Patriotic War of 1941-1945 and the fight against “Ukrainian Nazis” in 2022. The result of the propaganda has been so overwhelming that within six months, Sofia yelled at me that she cherishes the memory of her grandparents, which is why she is a patriot and stands with her country.

“My parents raised me in such a way that I cannot betray their memory, you understand?” she concluded.

Sofia and her family, immersed in Russian propaganda, have gone from horror and resignation to aggressively attacking those who disagree with the war in Ukraine, using the memory of their grandparents as arguments.

“No one needs us. That’s why I don’t care about anyone else. We have to get through all of this, and then we’ll see,” she firmly believes.

Note: *Names have been changed for privacy reasons.