The example of Vladimir Putin’s presidency vividly demonstrates that when power remains unchallenged through elections, populism becomes critically dangerous for a country. Putin has been in power for twenty-three years, and we can identify all three classic features of populist governance within the Russian government: the monopolization of the state apparatus, corruption and clientelism, and systematic suppression of civil society. Clientelism refers to the exchange of material goods and patronage by officials in return for their loyalty.

Populist Tools in the Putins’ Policy in Russia

This paper is a part of the discussion about dangerous populism for developed democracies and deadly for young, fragile democracies. We argue that populist tools are also used by authoritarian leaders to not only gain but also retain political power, which destroys democracy and leads to major geopolitical mistakes and economic decline. This paper will show you exactly what populist tools Putin has used and is using to stay in power at the cost of destroying democracy and Russia's economy

The example of Vladimir Putin’s presidency vividly demonstrates that when power remains unchallenged through elections, populism becomes critically dangerous for a country. Putin has been in power for twenty-three years, and we can identify all three classic features of populist governance within the Russian government: the monopolization of the state apparatus, corruption and clientelism, and systematic suppression of civil society. Clientelism refers to the exchange of material goods and patronage by officials in return for their loyalty.

However, Putin’s populism has its peculiarities.

1

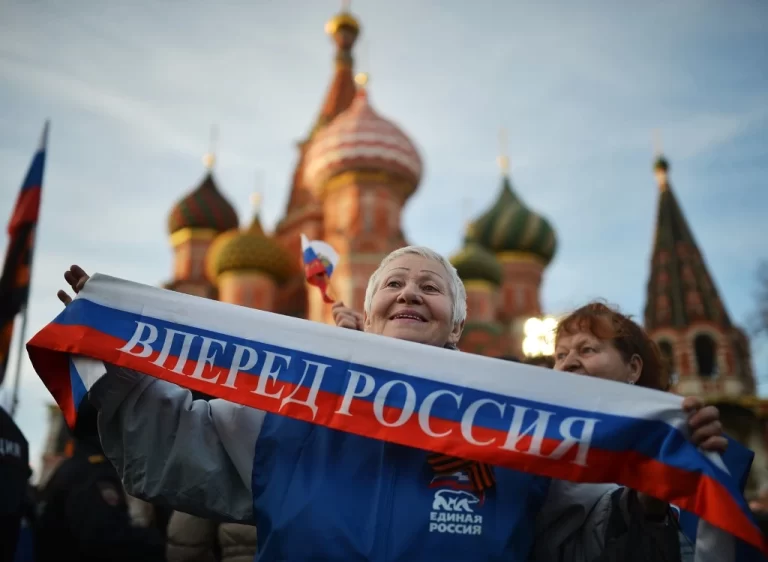

Firstly, Putin came to power in 2000 using standard populist tactics but then developed a populist approach to state governance. The core of his policies formed a ‘Putin majority,’ playing the role of a “united people” whose interests Putin purportedly protects.

2

Secondly, as the defender of the people, the president opposes two antagonists simultaneously: corrupt officials and oligarchs on one side and the threat of Western liberal democracy on the other.

Within the country, the president operates outside the branches of power and is non-partisan. That is, he is a leader separate from the political elite. Sometimes, Putin publicly punishes the ‘bad boyars,’ meaning officials and oligarchs, through high-profile anti-corruption campaigns. There is a constant demand for such public chastisement within society because 75% to 85% of Russians over the past 30 years considered state power corrupt.

Additionally, the president never participates in pre-election debates for two populist reasons: on the one hand, he is the leader of the country, elevated above other politicians alongside the people; on the other hand, Putin embodies the valid will of the people, which is not discussed in debates.

The confrontation with the “collective West” is based on the propagandist thesis of alienating Western liberal values from Russia and its traditions. It is also based on the affirmation, voiced by Russian Emperor Alexander the Third in the late 19th century, that Russia has no friends and is feared for its vastness.

3

Third, Putin loves referendums. All populist governments use referendums not to initiate public discussion and ascertain the will of the people but to validate decisions already made by the president. Referendums were held on the annexation of Crimea in 2014, the amendment of the Russian Constitution in 2020, and the inclusion of four Ukrainian regions into Russia in September 2022.

4

The fourth characteristic of Putin’s populism lies in the developed system of state financial benefits. Against the background of the poor quality of life of a significant part of the population, the government is expanding social programs and distributing money before elections. For example, the Russian people received the tradition of distributing 10,000 rubles per child to families before the start of the new school year. This is a convenient tactic for increasing voter loyalty before elections, annually in Russia in September.

5

Fifthly, Putin’s team has created a vast network of artificial civil society institutions in Russia, which the government fully controls. For example, since 2001, Putin has held a “Live Broadcast” with people, where the president sits in a studio, and every Russian citizen can ask him a question live on air and receive an answer. These annual events are extensively announced in state media and broadcast in real time. However, the government carefully prepares for the “Live Broadcast” by preselecting the most convenient questions from citizens and only including them in the script. No improvisation! The event aims to demonstrate the “good president’s” openness to ordinary people and his readiness to address issues that “bad officials” failed to handle.

Additionally, the president’s direct connection with citizens, bypassing officials, is demonstrated through public reception offices that operate under regional governments in each subject of the Russian Federation and receive letters addressed to the president.

In addition to the pseudo-communication with the president as a form of direct democracy, in 2004, the Russian government established the Public Chamber and a network of Public Councils within the state authorities in regions. These institutions substitute genuine civil associations. It is legislatively stipulated that Public Councils should be formed on a competitive public basis, control the executive power, and provide expert assessments of its decisions. On the one hand, the Russian government has collected civil activists into organized groups to collect information about public problems that may affect the president’s ratings and, on the other hand, to monitor the activists’ work.

The Russian government established the All-Russia People’s Front (ONF) in 2011. This organization is directly subordinate to President Putin. The organization gathers information about housing, utilities, urban improvement, road conditions, schools, and others and compels local officials to do their jobs. The ONF is not subject to regional authorities and is financially independent. However, very soon, the political tasks of maintaining positive images of governors ceased to align with the statutory goals of the ONF and their work methods. This led to a system of agreements between regional authorities and ONF activists. Thus, the closed Russian bureaucratic system absorbed this communication channel with society. Currently, the ONF is focused on collecting humanitarian aid for mobilized Russians and sending it to the front in Ukraine.

6

The sixth characteristic of Putin’s state populism seems ordinary. It is anti-pluralism, which manifests in the struggle against independent media and the persecution of opposition civil activists who speak out against the war in Ukraine. Here, the Kremlin implements the classic populist thesis of the unity of the people and Putin, creating the notion that anyone who opposes Putin is against the people. This idea even gave rise to a Russian slogan voiced in 2014 by the then Deputy Chief of the Presidential Administration, Vyacheslav Volodin. “If there is Putin, there is Russia; if there is no Putin, there is no Russia,” – he said.

7

However, Putin uses a dual strategy. He deceives the loyal people through media propaganda and encourages them financially. But he intimidates opposition citizens with punishment and forces them to leave the country. Those who do not go are fined, severely searched, and imprisoned.

As a result of the degradation of governance quality, significant geopolitical mistakes occurred in the Russian government. The Kremlin lost channels for receiving timely information due to the increasing isolation of the state system, which led to decision-making errors. After Crimea’s swift and bloodless annexation in 2014, Putin’s approval rating rose above 80%. The war in Ukraine in 2022 was supposed to be a “small victorious war” to maintain the extremely high rating of the Russian president, but it turned into a catastrophe.

The Russian government still uses the war in Ukraine to unite the “people” around the president despite failures on the front lines. Western European sanctions support the Kremlin’s public thesis of the West’s hostility towards Russians. Propaganda also plays a role. For example, Putin demonstrates “victories” in the war. In September 2022, the population was solemnly informed about incorporating four Ukrainian regions into Russia. In May 2023, the capture of the Ukrainian town of Bakhmut was announced after bloody battles. In turn, the human casualties and destruction in Ukrainian cities are presented as the consequences of the Ukrainian army’s actions.

By studying Russia as an example, US and European voters can recognize the detrimental effects of populist governance and be more vigilant in their own countries’ elections. Ultimately, the popularity of populists in the United States and Europe might decrease due to the situation in Russia.

Also on the topic: The Deadly Populism of President Putin in Russia