After HAMAS’s assault on Israeli territories and the bloody incidents publicized on the first day of the latest round of the Israeli-Hamas clash, international attention shifted from the Ukrainian war to the Israeli conflict. The media broadcasted videos of a festival massacre near the Gaza Strip, kidnappings, and maltreatment of women. For the first time in eighteen months of the Ukrainian war, Hamas militants, not Russian troops, emerged as the predominant culprits and “cannibals.”

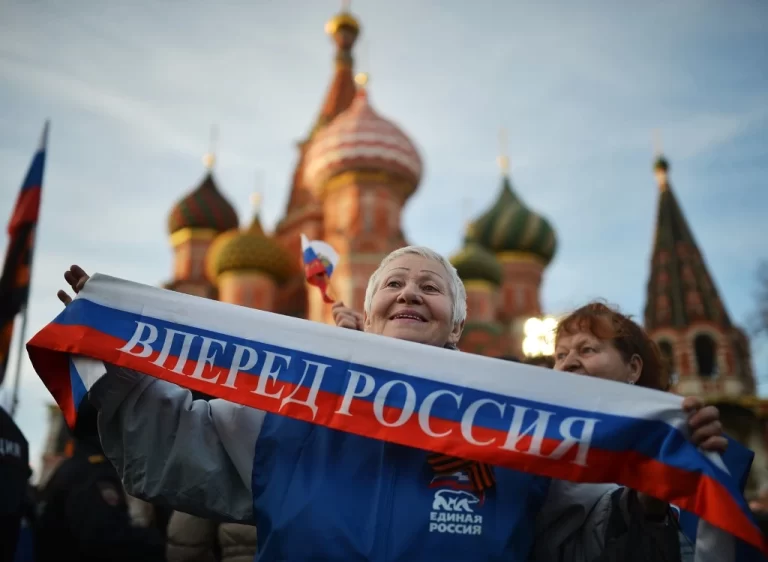

How the War in Israel Has Affected Russian Society

Many Russians experience a sense of moral relief following the conflict in Israel. Here’s why.

After HAMAS’s assault on Israeli territories and the bloody incidents publicized on the first day of the latest round of the Israeli-Hamas clash, international attention shifted from the Ukrainian war to the Israeli conflict. The media broadcasted videos of a festival massacre near the Gaza Strip, kidnappings, and maltreatment of women. For the first time in eighteen months of the Ukrainian war, Hamas militants, not Russian troops, emerged as the predominant culprits and “cannibals.”

Amid the overarching backdrop of Western Europe’s aggressive rhetoric and international sanctions against all Russians based on citizenship, Russians find solace in the thought that “we’re not the only bad guys” and others are even worse. This sentiment brings genuine relief to the average Russian citizen.

Moreover, the schadenfreude felt by those Russians who cannot leave the country is palpable when public figures who either fled to Israel to escape the war or acquired Israeli citizenship – like Andrey Makarevich, Ksenia Sobchak, Maxim Galkin, Alla Pugacheva, among others – are criticized and ridiculed. This situation exemplifies a psychological paradox where individuals deprived of dignity direct their hate not at those who deprived them but at those who managed to retain theirs. Hence, when these emigrants, largely reviled by most Russians, face issues, it satisfies the Russian public. As a Russian saying goes, “It doesn’t matter if you don’t have a cow, as long as your neighbor’s cow dies.

Official statements and propaganda further fuel Russian public sentiment. Kremlin-backed media outlets have been openly derisive towards the Israeli military and Russians who have relocated to Israel. These Russian news sources take a schadenfreude approach, suggesting that the “traitors” fled Russia only to find war awaiting them in Israel. To give a flavor of such reports, here’s a quote about Ksenia Sobchak:

“Recall that in ‘escaping her own country,’ Ksenia acquired Israeli citizenship to avoid living in a nation at war with its neighbors.’ Yet Sobchak doesn’t seem in a hurry to defend her ‘new homeland,’ just as she was slow to support her old one.”

Furthermore, the Russian embassy in Israel has outright stated that any considerations of evacuating Russian citizens from Israel are premature. Those wishing to leave should do so independently, given that regular flights remain operational.

Instead of fulfilling their duty to protect Russian citizens abroad, state representatives are once again issuing threats. Vyacheslav Volodin, the Chairman of the State Duma of the Russian Federation, has warned that those returning to Russia would face criminal prosecution.

“When we talk about relocators, those who left the country and acted maliciously, celebrating attacks on Russian soil and wishing victory to the bloody Nazi Kyiv regime, should realize they are not only unwelcome here, but if they come back, Magadan awaits them [It means prison – author’s note],” stated Chairman Volodin. His declaration can be found on the official website of the legislature.

With their choice of words, Russian public speakers seem to be catering to a psychological need among most Russians residing in the country. This need is to justify their passivity and vulnerability by collectively condemning and vilifying expatriates, whom they derogatorily refer to as “relocators.” It’s no coincidence that in official statements and media broadcasts, words like “relocator” and “those who left” are often paired with terms such as “traitor,” “betrayer of the homeland,” and someone who “wishes defeat” upon Russia and revels in bombings of its territory—even though these associations are factually incorrect.

In the minds of average Russians consuming television news, a narrative is instilled: a Russian who leaves is a traitor, while those who remain are loyal patriots.

This aggressive stance towards expatriates resonates with the Russian populace, as evidenced by reactions on social media. For instance, in the Russian segment of social networks, jokes are shared mocking those who moved to Armenia or Israel, suggesting they might as well consider relocating to Taiwan or South Korea next. A popular quip reads: “For those who moved ‘far from war’ to Israel and Armenia, there are still two quite calm and serene places left for relocation. You’re welcome.”

Another trending post in Russian social channels states, “Rats that fled the ship are infuriated that the ship refuses to sink.” In this metaphor, the “rats” symbolize Russians who left the country following the onset of the war in Ukraine, and the “ship” represents Russia itself.

Consequently, Russians continue to rally around a political regime that increasingly exhibits terroristic tendencies towards its citizens, whether they are domestically located or abroad. As they witness the persecution of Russian citizens overseas and escalating localized military conflicts, they conclude that there is no haven in the world—especially not for them. This realization prompts continued resilience and determination to endure the ‘challenging times’ ahead.