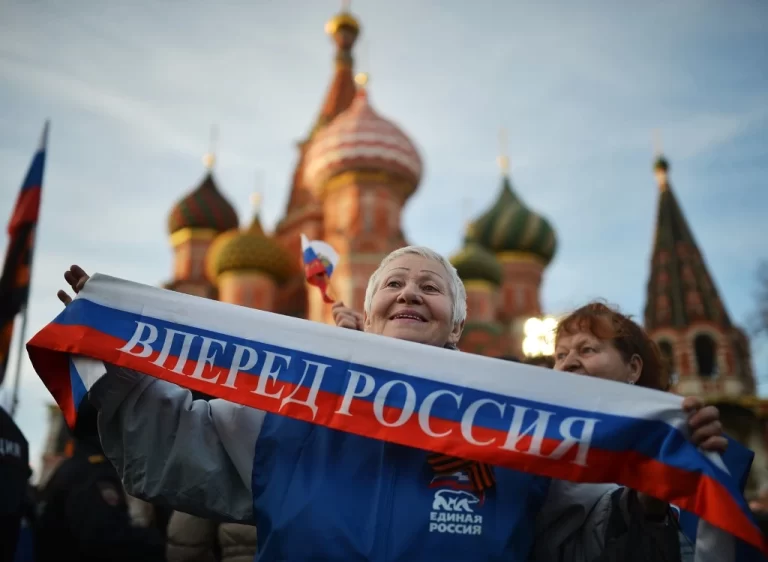

Authoritarian Russia: The Birthplace of State-Driven Populism

Russia's experience illustrates that populism is not solely a flaw of democracy. On the contrary, the foundations of populism were established and evolved under the autocratic monarchy in Russia. Thus, populism serves as a tool for both seizing and maintaining power, irrespective of the political regime or forms of governance. Let's dive deeper into Russian history, where we will find confirmation of our assertion

Since the 10th century, favorable conditions were formed in Russia for the flourishing of populists. In 988, Grand Prince Vladimir of Kyiv chose the Orthodox Church for Russians. After the Ottoman Empire conquered the fall of Constantinople in 1453 and the Balkans, Russia became the only independent Orthodox country surrounded by “enemies” from other Churches.

Tsar Ivan III, who centralized Russian lands around Moscow at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, made a significant political move to strengthen his power. In 1472, he married Sophia Paleologue, the niece of the last Byzantine Emperor Constantine the Eleventh. From that moment, he elevated himself above other Russian princes and acquired imperial ambitions as the sole successor to the Byzantine Empire. Under Ivan III, Russia transformed from a confederation of independent Russian lands into a centralized Eastern Empire. Although, in Russia, the Orthodox Church has established that power comes “from God,” Moscow has a unique goal – to protect the Orthodox faith.

Ivan the Terrible, the grandson of Ivan III, unleashed bloody repressions against the political elite (“boyars”) known as the “oprichnina.” The Oprichnina policy implemented by Ivan the Terrible from 1565 to 1572 was essentially a terrorist despotism. The tsar divided the country into two parts. One part was declared the tsar’s property, which included the most developed and protected lands, safeguarded against invasions by Lithuanians, Poles, Swedes, and Crimean Tatars. The remaining territory of Russia was declared the “zemshchina” and was obligated to support the Oprichnina lands. The political elite who owned lands within the Oprichnina territory were stripped of their property and relocated to the outskirts of the country.

The tsar created a personally loyal army composed of lower-class individuals to protect his possessions. They were named “oprichniks.” The primary condition for joining the Oprichnina army was the absence of blood or business ties with the boyars and personal loyalty to the tsar.

During the reign of Ivan the Terrible, the populist formula “boyars are bad, and the tsar is good” emerged, aimed against the political elite. In this context, the unpunished crimes committed by the oprichniks, who were loyal to the tsar, instilled in the minds of Russians a wariness of pluralism because the loyal oprichniks could do whatever they wanted. At the same time, disloyal boyars faced expulsion or torturous death. The impact of the Oprichnina on the formation of obedience among Russians was strengthened by serfdom, which was abolished in Russia by Emperor Alexander the Second in 1861.

Moreover, the Russian peasants, who constituted over 80% of the population of Russia, lived in communities. They worked and cultivated the land together to survive in harsh weather conditions. In this context, the community’s interests precede individual needs. Collaborative thinking led to Russians’ inclination towards conformity, accepting the majority’s will, and recognizing collective goals. From this stemmed the desire for unity of opinions and the rejection of opposition.

The central tenets of populism were finally formulated in Russia during the reign of Emperor Nicholas I. In 1833, Minister of Public Enlightenment Sergey Uvarov established the state doctrine of “Official Nationality.” The short slogan of this theory read as follows: “Orthodoxy, Autocracy, Nationality,” and was formulated as a counterpoint to the French Revolution’s motto, “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity.”

The state doctrine of “Official Nationality” proclaimed the national distinctiveness of Russia, the unity of the tsar and the people, and the mission of the Russian state to protect the Russian people from Western liberalism and democracy.

The ideas of “Official Nationality” inspired some Russian writers and philosophers of the 19th century in their search for a unique path to Russia’s development and national self-determination. This resulted in the religious and philosophical movement of Russian public thought within the framework of conservative romanticism, known as “Slavophilism.”

President Vladimir Putin is also influenced by the ideas of Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality, the unity of the people with the “tsar,” and the cultivation of the image of the external enemy in Western liberalism.

Thus, the foundational ideological tenets of populism were laid down in Russia by Tsar Ivan III, emphasizing Russia’s unique role as the sole country with an Orthodox faith surrounded by hostile non-believers. Populist strategies of distinguishing the leader from the political elite and crafting the image of the Tsar as a representative of the people’s will and protector of the commoners were introduced into Russian political culture by Ivan the Terrible. Finally, under Nicholas I, these populist inclinations were formalized into the state doctrine of “Official Nationality,” the postulates of which are now embraced by Russia’s current president, Vladimir Putin.